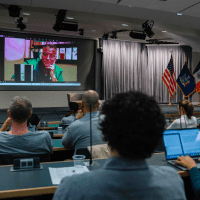

On October 15, 2025, CUNY School of Law hosted a conversation that bridged the walls of Sing Sing Correctional Facility and a law school auditorium in Long Island City. Prison journalist John J. Lennon joined Professor Steve Zeidman virtually to discuss his new book, The Tragedy of True Crime: Four Guilty Men and the Stories That Define Us. Lennon is a two-time National Magazine Award finalist and regular contributor to The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The New York Times Magazine.

Lennon, who is serving his twenty-fourth year behind bars and is a client of CUNY Law’s Defenders Clinic, spoke candidly about the incongruity of America’s insatiable appetite for true crime content and the realities of mass incarceration. His book examines four men who have committed homicide—three of whom are represented by the clinic’s Second Look Project. Through his perspective, Lennon offers intimate narratives that challenge sensationalism and advocate for reconsideration of lengthy sentences.

The True Crime Paradox

Lennon opened the conversation with Professor Zeidman by sharing a striking observation: true crime obsession is surging even as crime rates hit historic lows, yet public perception is that crime is rising. “Fifty-seven percent of people watch murder content before bed,” he noted. “No wonder they wake up and think ‘Thank God we have all these prisons.'”

This disconnect, Lennon argued, has real consequences for clemency advocacy. When violence becomes entertainment in the form of podcasts, streaming series, and viral videos, it becomes harder to see incarcerated people as fully human, capable of transformation and deserving of second chances. “The world delivers the facts,” Lennon explained. “It’s the narrative journalist’s job to render them. I have a different agenda—I want to show you the fuller story.”

Death By Incarceration

Lennon and Professor Zeidman discussed New York’s particularly harsh sentencing structure. Professor Zeidman explained that sentences of fifty years or more amount to “death by incarceration,” and, unlike other states, New York requires individuals to serve their full sentence before becoming eligible for parole. “Even in blue New York,” he emphasized.

Lennon spoke poignantly about people in prison facing these extreme sentences: “They live in the law library, sometimes to the point that it’s delusional.” He described Michael Shane Hale, one of the men featured in his book and a client of the Defenders Clinic, who received fifty years for killing someone he loved. “You can’t live in that bitter kind of space… and Shane doesn’t,” Lennon reflected. “Pride and shame are two sides of the same coin. Every equation is remorse.”

Lennon also addressed how the unlikely odds of receiving clemency in New York can lead to hopelessness in prisoners and discourage efforts to reform. “If you give the stick and don’t offer any carrots, what’s the incentive?” he asked.

Clemency Work at the Defenders Clinic

Lennon’s case exemplifies the real-impact work of CUNY Law’s Defenders Clinic and its Second Look Project. The project focuses on clemency and parole petitions for individuals who have demonstrated genuine transformation during lengthy periods of incarceration. To date, the Second Look Project has worked with more than 200 individuals and has helped bring home 84.

Working with clients like Lennon requires navigating complex questions about accountability, redemption, and identity. As Professor Zeidman noted, Lennon advocates for seeing people as fully human while rejecting simplistic narratives that incarcerated people become entirely “different people” over time. Lennon acknowledged this tension: “Realistically if you kill somebody it’s pretty far reaching.”

A Call for Different Stories

Professor Zeidman closed the evening by reading from Lennon’s book: “True crime turns back the clock and replays the worst moments of someone’s life, reconstructs and reenacts it all for entertainment, usually by exploiting the people most affected by the violence—victims whose wounds haven’t healed, perpetrators who haven’t reckoned with their guilt.”

Lennon’s work, both his book and his ongoing advocacy, offers an alternative. By telling fuller, more complex stories, he challenges us to reconsider not just individual cases, but the entire systemic structure of punishment in America.

John J. Lennon will be eligible for parole in 2029.